Heat Related Illness

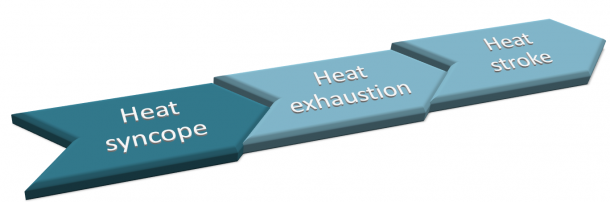

Heat related illness presents in a spectrum from minor (oedema, cramps, tetany, prickly heat), to the more serious (syncope, exhaustion and stroke).

Management is directed at reversing the process and treating sequellae if they arrive.

Risk factors for developing heat related illness

- high temperature and high humidity

- infants (perspire less than adults)

- elderly (have reduced thermoregulation)

- obesity

- dehydration

- alcohol use

- increased activity

Physiological responses to heat:

- vasodilatation of skin capillaries causing heat loss by radiation to air

- increased sweat production causing heat loss by cooling due to evaporation

- decreased heat production to aim to decrease the Basal Metabolic Rate (BMR)

- behavioural response (seek shade, less clothing, cool shower, swim, etc.)

Minor Heat Related Illness

Heat Oedema

- oedema of hands, feet and ankles

- usually occurs in the first few days of acclimatisation to heat

- more common in females and in the elderly

- no treatment is needed apart from reassurance that this will settle in time

- advice to elevate feet with foot and ankle mobilisation

Heat Cramps

- cramping in muscles, most often in the calves

- usually occurs on stopping exercise

- due to hypovolaemia and salt deficiency

- exacerbated by drinking water but no salt leading to progressive minor hyponatraemia

- treated with rest, fluid and salt replacement

- oral rehydration solutions

- if severe may need IV normal saline

Heat Tetany

- caused by hyperventilation after exposure to extreme heat

- leads to paraesthesia (usually circum-oral and in hands and feet)

- muscle spasm in hands and feet (carpopedal spasm)

- treated by removal from heat and reassurance

Prickly heat

- itchy erythematous rash

- blockage of sweat pores causing inflammation of sweat ducts

- it occasionally more chronic dermatitis

- treatment is by heat avoidance, wearing light, clean clothes and soothing lotions (e.g. calamine)

Heat Stroke

Historically there is often an obvious precipitant, such as a marathon or working in hot conditions. If not environmental, is it a toxidrome such as an anticholinergic or sympathomimetic. Other useful historical points to consider include what were the methods of fluid replacement - was it water alone (excessive water intake leading to hyponatraemia) or sports drinks (better but often have insufficient sodium for heavy sweating conditions).

Heat stroke should be considered in any patient with exposure to heat and an altered conscious state or confusion.

Note: Core temperature should be measured with a rectal thermometer for the most accurate readings.

Note: Core temperature should be measured with a rectal thermometer for the most accurate readings.

The classic findings are:

- high temperature (usually >40°C)

- hot and dry skin (sweating is usually absent; sometimes skin is cold due to shock) neurological abnormalities.

Neurological abnormalities include:

- ataxia

- confusion

- coma

- convulsions

- High mortality of 15-80%, especially if untreated or delayed treatment

Other typical findings:

- tachycardia

- hypotension (especially with a postural drop)

- hyperventilation.

Investigations

- Urinalysis – myoglobin in rhabdomyolysis

- ECG - tachycardia, tachyarrythmia, which may be elctrolyte or drug related

- BSL - may be low in decreased LOC or high in sepsis, DKA, or any intercurrent infection.

Laboratory

May be normal or may show:

- hyponatraemia

- hypokalaemia early, with hyperkalaemia if rhabdomyolysis develops

- hypercalcaemia early, with hypocalcaemia if rhabdomyolysis develops

- metabolic acidosis

- Increased creatine kinase (CK) – often 10,000 to 1,000,000

- Renal impairment

Management

- Management in cool area, exposed.

- ABCDE.

- IV analgesia and fluids via x2 large bore cannulae.

- Call for help early.

- Active airway management such as intubation should be performed early for airway obstruction (especially in the unconscious or fitting patient).

- Generous fluid resuscitation with normal saline, especially if rhabdomyolysis develops, as severe dehydration and renal failure may be present. Avoid fluids containing potassium or lactate.

- Close haemodynamic monitoring is essential, and vasopressors may be needed for hypotension (dopamine is preferred as catecholamines may impair heat dissipation)

- If no ICU is available, call for medical retrieval early; do not wait as the patient gets sicker and sicker.

- Suxamethonium should be avoided as this may exacerbate the dysrhythmic properties of hyperkalaemia.

- There is no role for antipyretics like paracetamol or ibuprofen. Dantrolene has also been shown to be ineffective.

Cooling techniques

- Use passive / evaporative cooling - this consists of sponging or spraying the skin with tepid water and putting fans onto the patient.

- Ice packs to the axillae, groin and around the neck.

- Cooling blankets can also be used, caution with wrapping in cool wet towels as they heat up and insulate quickly, avoid this method.

- Immersion in cold water baths if possible, but beware in patients with altered consciousness / confusion. Ice water baths are recommended but may not be tolerated by conscious patients (and may not be practical in sicker patients).

- For severe cases and very sick patients central / active cooling can be used, with cold water lavage via:

- urinary catheter

- nasogastric tube or rectal tube

- thoracic or peritoneal lavage

- cardiopulmonary bypass (if available) has also been used for life-threatening cases.

- Cooling measures should be ceased once temperature reaches around 38°C to avoid overcooling.

Further Treatment

- Medications may be needed to stop shivering, such as diazepam initially. In severe cases, if there are still difficulties with cooling the patient, non depolarising muscle relaxants may be needed.

- Urinary output should be maintained above 1-2mL/kg/hr (ensure enough fluid resuscitation is given to enhance this).

- Although excessive fluid can lead to pulmonary oedema in heatstroke patients, it is part of management of rhabdomyolysis if this is present.

- Urine alkalinisation with IV sodium bicarbonate, mannitol and loop diuretics such as frusemide can been used. Volume status should be monitored invasively when patients are this sick.

- Dialysis may be required for renal failure, especially if developing acidosis or hyperkalaemia.

The longer treatment to decrease the temperature is delayed, the more mortality increases. This may lead to rhabdomyolysis and renal failure.

Further References and Resources

- Khan, F.Y 2009. Rhabdomyolysis: a review of the literature. Netherlands Journal of Medicine. vol. 67, no. 9, pp 272-283.

- Medscape – Heatstroke Treatment and Management (login required)

Heat Exhaustion

Occurs due to water and sodium depletion, dehydration and hypovolaemia from heat stress.

Temperature can be normal or up to 41°C and will be alert with normal neurology.

Patients will have:

- Sweating

- Weakness

- Fatigue

- Nausea

- Vomiting

Examination may also reveal:

- Tachycardia

- Tachypnoea

- Dehydration

Management:

- Cool environment, rest

- ABCDE approach ( if requires A and B support then treat as per heat stroke, fluid bolus 20 ml/kg if dehydrated)

- BSL (treat if low with sugar)

- Observe for any signs of heat stroke ( is the patent neurologically normal)

- Rehydrate with either oral rehydration solutions or IV normal saline

- If temperature >40°C then active cooling measures will be required

Heat Syncope

A transient loss of consciousness followed by a full and rapid recovery. This can be possibly vasovagal, or due to transient postural hypotension (due to peripheral vasodilation secondary to heat).

Often patients will have prior symptoms of:

- Vertigo

- Dizziness and nausea

- Visual disturbance

Management

- Cool environment and rest (lie down)

- ABCDE approach

- Observe for any signs of heat exhaustion and heat stroke

- Oral fluids